The Mola Museum is a “virtual museum” dedicated to the art of the Kuna (Guna) Indians. The Kunas live on the San Blas Islands east of Panama, in the Darien region of Panama, and in Colombia. Kuna women make and wear blouses decorated with appliqued cloth, reverse appliqued cloth and embroidery. The blouses, and their decorative front and rear panels, are referred to as molas. The best molas are remarkable works of art. The Mola Museum is dedicated to promoting this amazingly diverse art form. Our collection focuses on molas and other Kuna art made prior to 1975.

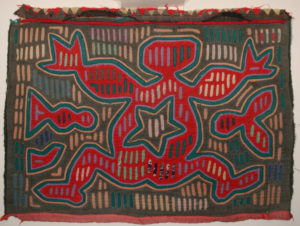

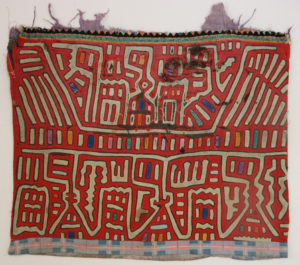

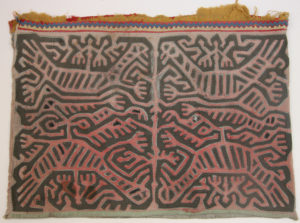

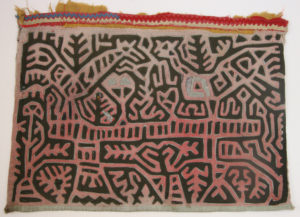

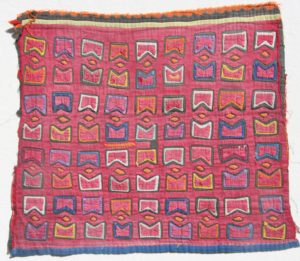

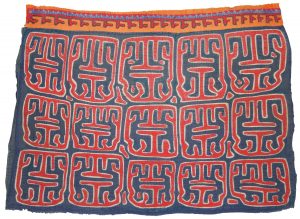

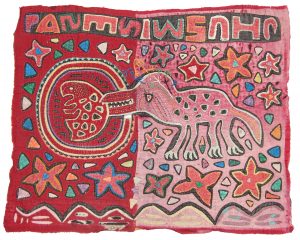

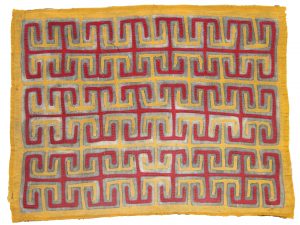

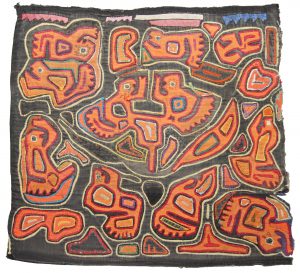

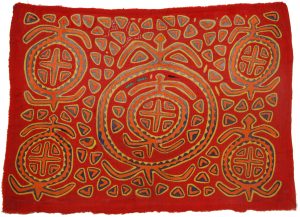

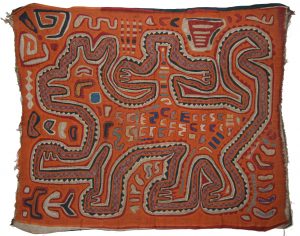

Abstract & Spiritual Molas From The Collection of Ann Parker and Avon Neal.

In 1977 the first “coffee table book” about molas was published. Molas was the joint effort of Avon Neal and Ann Parker, a husband-and-wife team that published a number of books about various art forms. For many mola collectors, their book was a jumping-off point. We read the book and “got the bug.” Ann’s splendid photography and Avon’s diligent, time-consuming, pre-internet research created a game-changing publication.

Ann and Avon’s taste in molas provided guidance for a lot of us. Their focus was clearly aimed at “story-telling” molas, often those that were inspired by photographs and drawings in magazines, newspapers and books from the U.S., Mexico and Europe. But their mola collection also included a large number of abstract and spiritually-focused molas. We have been fortunate to get to know Ann quite well (Avon has passed away), and have acquired a number of pieces from their collection. Shown here is an assortment of traditional (vs. acculturated) molas from the collection of Ann Parker & Avon Neal.

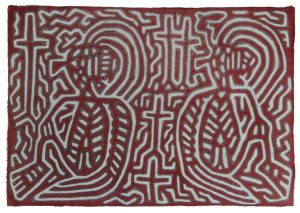

Nuchu Carvings Depicting Clergy or Courtly Figures.

Nuchugana (the plural of nuchu) are carved wooden figures used in spiritual healing ceremonies by the Guna* Indians. The figure is actually considered a storage vessel for a healing spirit that is summoned by a Guna healer (Ina Tuledi) when someone is ill. According to Mac Chapin, an anthropologist who lived with the Gunas, most nuchugana are carved to represent “wakka” — non-Guna people. Most commonly based on American or European characters, the carvers frequently use powerful people as models. According to Kit Kapp, who spent 11 years exploring Guna territory, they believed that people in power could inspire powerful spirits. So frequently nuchu figures depict politicians (Eisenhower, Churchill, JFK), soldiers (Macarthur, Eisenhower), priests or royalty.

Below you will see a number of images from the last two categories — Christian clergy members and royal (or at least courtly) figures. We often can’t quite determine which is which, since both groups can dress similarly. Although a crown tends to be a tip-off that a nuchu represents a king. Some of the nuchugana in this dual category are quite elaborately carved. In fact some are so fine, one might suspect they were created by a Santo carver. And perhaps they were. The first two pieces were the prize nuchu figures in the collection of Avon Neal and Ann Parker, the couple who co-wrote the seminal book Molas. These are very “fancy” and appear to be very early, and very worn, examples that may date to the 19th century – and little is known about their origin. Ann Parker says that her husband, Avon, was forced to retreat to a remote part of an island to negotiate their purchase.

*Spelling of the name of this culture has evolved over the years. Originally “Cuna” was the most common name/pronunciation. In the 1970s that evolved to Kuna. But several years ago a vote was taken to change the spelling/pronunciation to Guna. On this site we will often use either Guna or Kuna — primarily because a) Guna is the most appropriate name but b) many people have never heard the word Guna – and get confused until Kuna/Cuna is used.

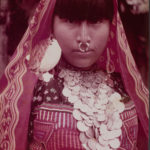

1960s San Blas Photos

Kit Kapp’s archives included a number of photographs of Guna Yala from the 1960s. Most of the shots are from the San Blas Islands, but some show Guna communities on the Bayano River in the Darien. We don’t know if Kit took these photos, or acquired them elsewhere. But many of the images are really touching, revealing the gentle humanity that is so much a part of these wonderful people. We also like the image of Kit at the wheel of the Fairwinds, the sailboat he lost in a tragic engine explosion off the coast of Colombia.

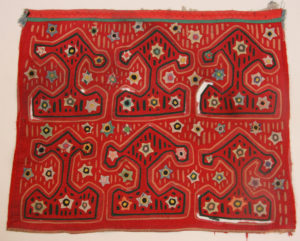

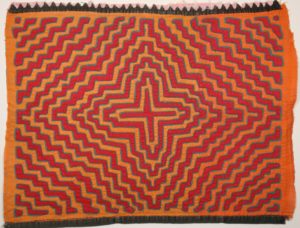

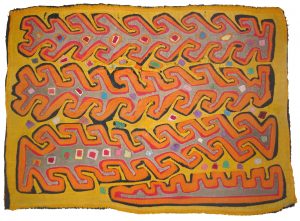

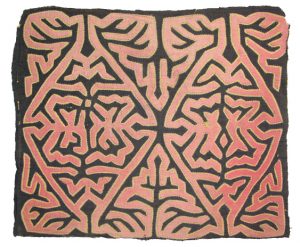

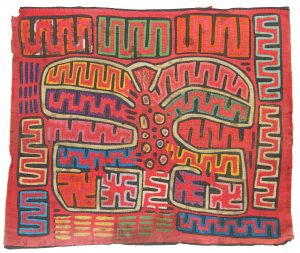

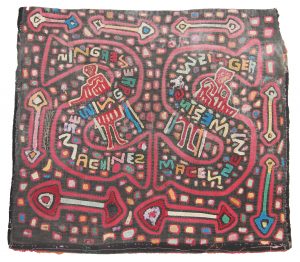

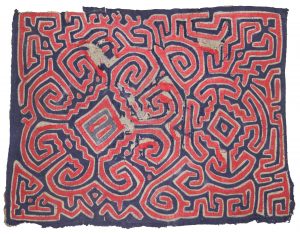

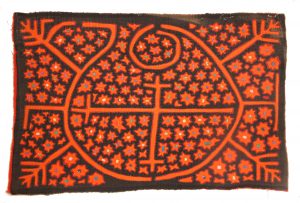

Fewer colors = greater molas?

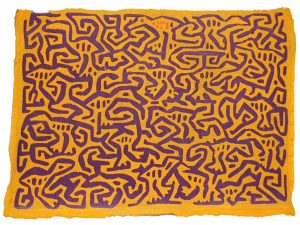

In Mari Lyn Salvador’s important book, Yer Dailege!, she surveys a number of Guna mola makers, asking them what makes for a good mola. The biggest criticism of their favorite mola was that it had “too many small areas of color.” We agree with these women. Sometimes the very best molas use a small number of colors. The result is often quite striking. Fewer colors often equals greater visual impact. Here are some examples we like.

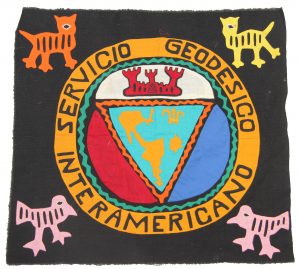

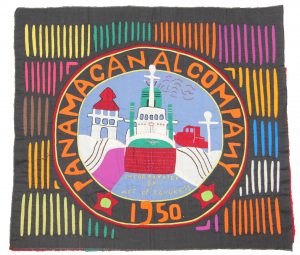

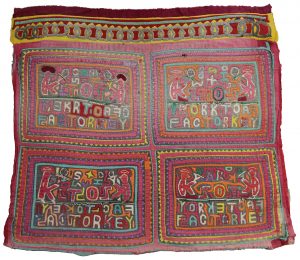

The Custom Mola Collection of General H. R. Parfitt

H. R. Parfitt was the Governor of the Panama Canal Zone from 1975 to 1979. Prior to that, from 1965 to 1968, he was lieutenant governor of the Canal Zone and vice president of the Panama Canal Company. Between those periods, he served in Vietnam. During his stay in Panama he commissioned at least three molas that replicated insigniae of the Panama Canal Company, the Panama Canal Zone and Servicio Geodesico Interamericano (the Inter American Geodetic Survey). We were lucky enough to acquire these three molas as well as a wall plaque and desk ornament from General Parfitt’s estate. The desk ornament was presented to him in 1968 when he was leaving for Vietnam. It is inscribed, “Presented to Lt. Gov. H. R. Parfitt by Dredging Division August 19, 1968 For An Unfaltering Trust In This Division’s Ability To Perform The Impossible.” Judging from the cloth used, and their general style (especially the use of small triangular “tas tas” filler ornaments), we’re guessing the molas were made in the latter part of Parfitt’s service in Panama — between 1975 and 1979.

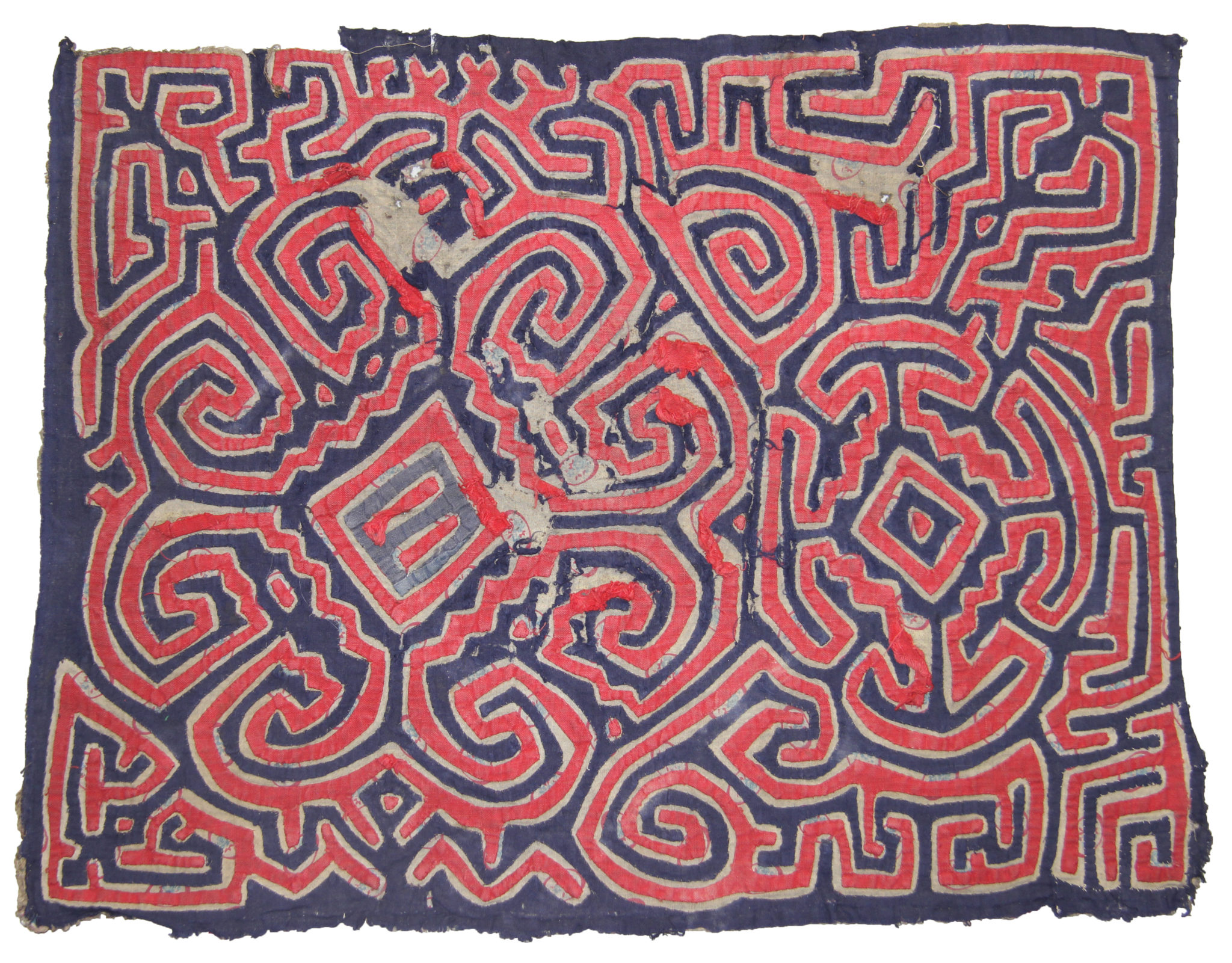

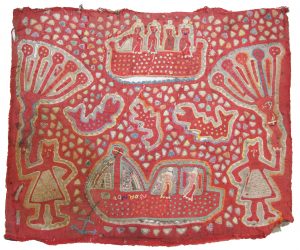

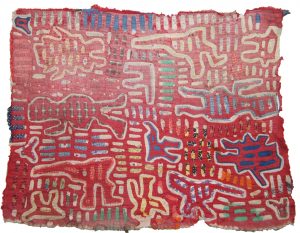

Stained, Torn, Faded Molas: Why Are They Beautiful?

Guna women have a high regard for their appearance. Most of them would never go out in public wearing a damaged or dirty mola blouse. When blouses are damaged, or simply wear out, they are normally disposed of. But Kit Kapp collected a number of molas that are in terrible condition. All kinda ripped, torn, burnt, stained, crazy-faded and full of holes. There is one thing they all have in common — they are great molas. Interesting. Beautiful. Intricate. The usually involved a lot of labor on the part of the artist.

So here’s our theory: when a Guna woman puts her heart and soul into a mola, it becomes an object of great pride. Something worth wearing, even when it’s damaged. It’s a good theory. We’re pretty sure we’re right. And we are very sure we’re glad that Kit had the insight to acquired these “damaged goods,” because they are awesome.

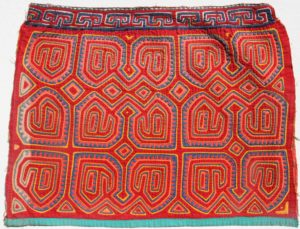

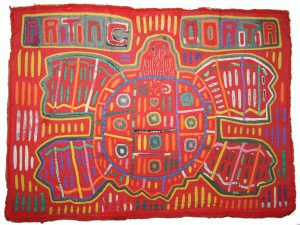

“When All Else Fails, Look For Turtles.”

Deciphering the imagery on older molas can be a challenge. One design element could be interpreted as a flower, a leaf, a star, an anchor, a ship’s steering wheel…or a turtle. A good friend and member of the Kuna Art Society once opined, “When all else fails, look for turtles.” Good advice.

Here we present a number of “Yauk” or turtle design molas from a variety of time periods. And yes, some of them might be abstract designs or steering wheels — let us know what you think.

Did molas evolve from body painting?

A commonly heard theory about molas suggests that they evolved from a tradition of body-painting. There is some evidence that Guna women might, at one time, have gone around topless with painted designs on their torsos — including one photo we have from the 1930s (which Facebook censors when we try to post it). But we have also seen rare paintings of Guna women from 1842 — and they are fully clothed. So the body-painting-to-mola-blou

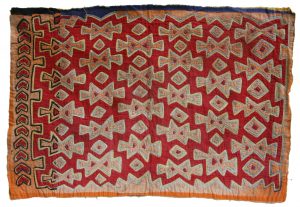

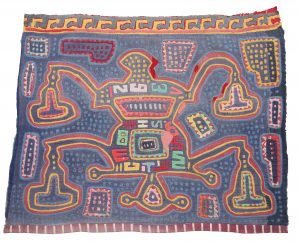

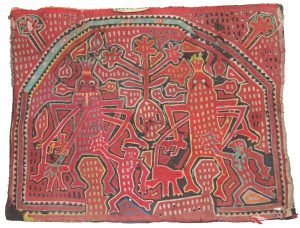

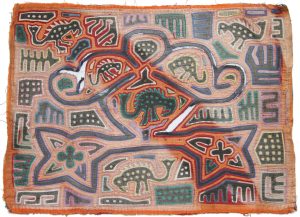

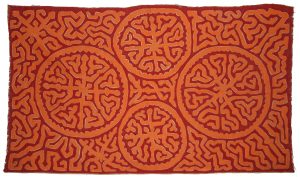

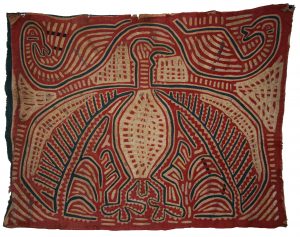

The Mystery of Gigantic Molas.

Modern molas are often 14′” – 17″ wide, because modern Guna women usually prefer a tight-fitting blouse. In the 1960s the average mola was 19″ – 21″ wide, because women then preferred a looser fit. In the 1920s and 1930s mola blouses were much larger, averaging 23″ – 25″ in width. There are some new mola panels being sold in Panama City that are the size of tablecloths — but those are clearly made for tourists. Far more interesting are huge molas made in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. The orange “purba” mola (showing a four legged animal with a being/spirit rising out of its back) is 26″ wide by 22″ high. It was likely part of a blouse of a larger woman. But the red/gold “batesor” mola (with large circular motifs) is 31″ wide by 18.5″ high — much too large to be a blouse panel. The blue eagle or “wekko” bird mola was collected in the 1920s by Captain Wayne Stukey and is 29.5″ x 22.5″…also too large to have been used in a blouse. And the large, yellow, vertically-oriented panel with a purba image and the abstract image of a winged monkey is 45.5″ x 22.5″!

There are similarly large, early examples of molas in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution. The question is, “How were they used?” We don’t know of any historical examples of the Gunadule people using mola textiles as wall-hangings, table cloths or “altar” coverings. So perhaps these gigantic mola panels were “made for us.” Specially crafted for sale to outside visitors.

For now, these “molagana dummat” remain a mystery.

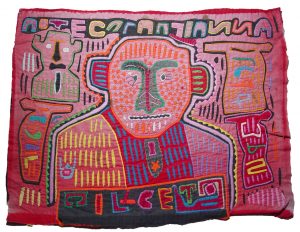

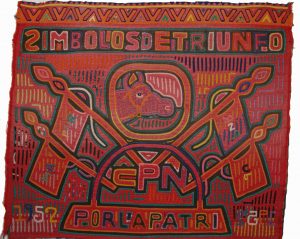

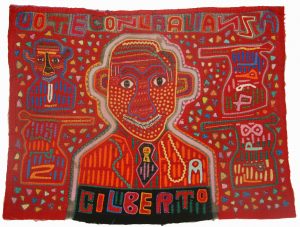

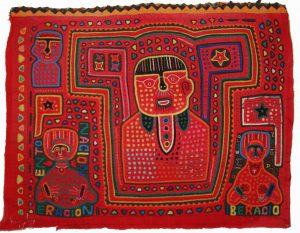

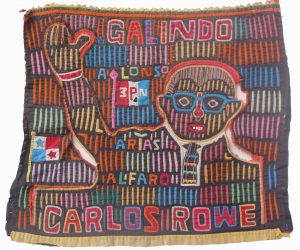

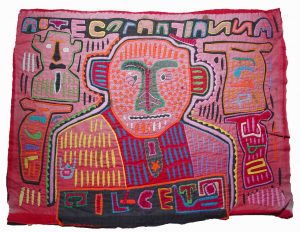

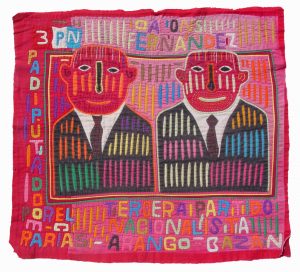

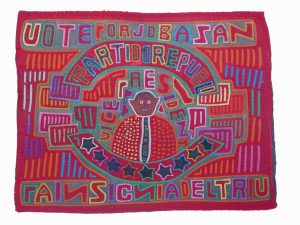

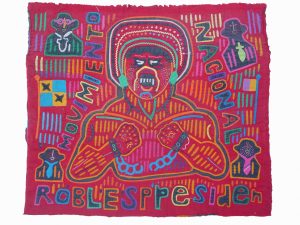

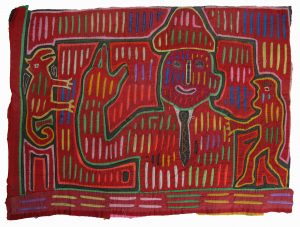

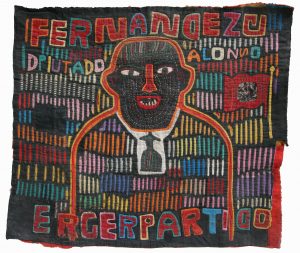

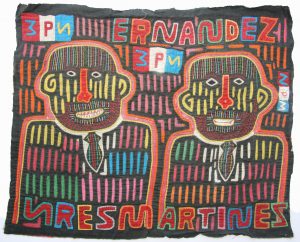

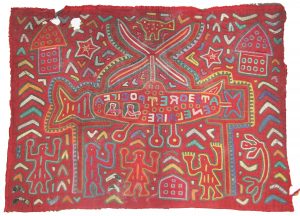

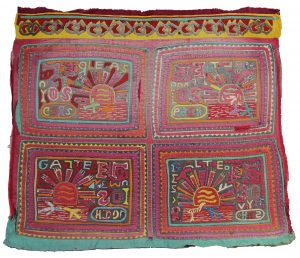

Political Molas

In the early 1960s, Panamanian politicians began soliciting Guna voters quite seriously. They came to Guna Yala to give speeches — and colorful posters were distributed, each one featuring the face of a candidate. These posters inspired Guna women to create molas replicating the political imagery. Many of these political molas had a light-hearted charm — the candidates became fun cartoon characters rather than serious demagogues.